From a £2bn hub close to the Mersey Vertex is to supply 1,000MW of hydrogen to big names such as Pilkington and Tata Chemicals – but question marks remain over the project. Tony McDonough reports

Vertex Hydrogen says it has now signed deals to supply 1,000MW of hydrogen to major industrial businesses in Liverpool city region and beyond.

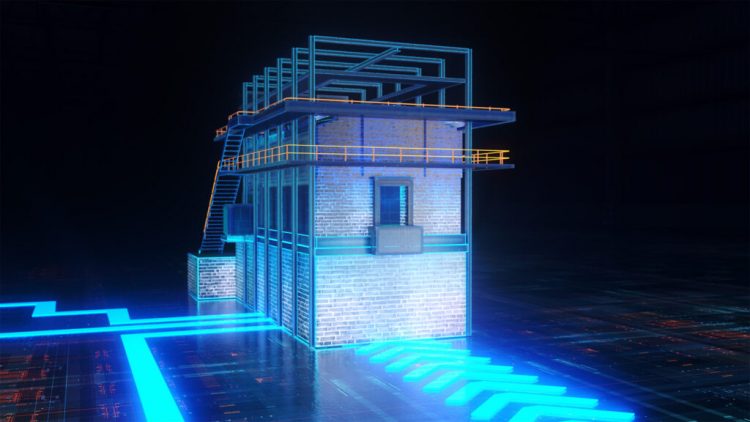

Backed by the Government, Vertex Hydrogen is a joint venture between Stanlow oil refinery owner Essar Oil UK and low carbon energy firm Progressive Energy, the hub forms part of the £47bn HyNet North West hydrogen project.

It will be located at the Essar refinery at Ellesmere Port, close to the River Mersey. 1,000MW of energy is enough to power a city the size of Liverpool.

St Helens glassmaker Pilkington, Tata Chemicals in Cheshire and glass bottle maker Enirc will all be supplied with hydrogen. SOG, owner of the Heath Business and Technical Park in Runcorn, has also signed up.

Hydrogen will be produced by burning natural gas, and waste fuel gases from Stanlow. The carbon produced via this process will be ‘captured’ by another HyNet partner, Eni SpA, and will be piped out to be stored in depleted gas fields under Liverpool Bay.

Due to be up and running by the end of 2025, the project will aim to capture around 1.8m tonnes of CO2 each year. This would reduce the region’s industrial emissions by more than 10% and is the equivalent to taking 750,000 cars off the roads.

Joe Seifert, chief executive of Vertex Hydrogen, said: “We have always said that Vertex is demand-led from leading industrial companies and we have now signed agreements for over 1000MW of hydrogen.

“It is our entire expected production capacity from the initial phases of our project. This milestone gives us huge confidence in the economics of the project and the long-term demand for low carbon hydrogen in the coming decades.”

Technical challenges

However, there remain big question marks over the project and whether it will live up to its promise to make a real contribution to the UK’s net zero targets.

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe and at the point of use it is emissions-free. But to obtain energy from hydrogen we first have to separate it from other elements in fossil fuels or water. There are a number of ways of doing this.

So-called grey hydrogen is hydrogen produced using fossil fuels, as above, but the resultant carbon is released into the atmosphere contributing to global warming and climate change. More than 70% of the hydrogen in the world is still produced this way.

At the other end of the scale is green hydrogen. This is produced by running electricity from renewable sources such as wind or solar through a machine called an electrolyser. It separates the hydrogen from water molecules.

This is by far the best way to produce hydrogen in terms of cutting carbon emissions. However, green hydrogen is currently expensive and not yet at the point where it can be sufficiently scaled up.

HyNet has chosen what it insists is a method that will allow the transition to green. Blue hydrogen is produced by burning methane, as detailed earlier in this article. The carbon is then captured and stored.

To reach the necessary efficacy to make it viable HyNet would have to capture at least 90% of the carbon. Similar scale projects elsewhere in the world have struggled to achieve more than 75%.

In an interview with LBN in 2022, HyNet project director David Parkin said he was confident it would achieve its capture targets when the facility is fired up in 2025.

Mr Parkin claims that unlike green hydrogen, blue hydrogen is scalable right now and can attract enough investment. He adds that all the infrastructure being put in place will be suitable for green hydrogen further down the line.

HyNet is investing in a number of smaller scale green hydrogen projects. It will utilise electricity from the Frodsham Wind Farm close to the Mersey Estuary.

Opponents of blue hydrogen claim it is a ruse by the fossil fuel industry to prolong the use of hydrocarbons in energy production. They also point to other emissions as part of the wider process.

In an interview with LBN, Abigail Dombey, a chartered engineer and chair of Hydrogen Sussex, said: “There has been a lot of work in the last year about fugitive emissions (leaks from pipelines or tanks) from natural gas as well.

“There are a lot more emissions upstream than we previously accounted for.”

Hydrogen at home?

How the hydrogen will be used is also causing some controversy. There is widespread consensus that the best use for hydrogen is for powering factories or larger modes of transport such as buses.

Liverpool City Region Metro Mayor Steve Rotherham will be introducing a fleet of hydrogen buses onto Merseyside’s roads in the first half of this year.

But HyNet is also participating in a trial to turn Whitby in Ellesmere Port into the UK’s first ‘hydrogen village’. In a partnership with gas network giant Cadent, 2,000 homes will use hydrogen for heating, cooking and hot water instead of natural gas.

This is seen by many experts as, frankly, an absurd idea. Compared to heat pumps, hydrogen is a much less efficient way of heating a home.

Earlier this week, the House of Lords Environment and Climate Change Commitee wrote to the Government expressing serious concerns about using hydrogen for domestic heating. It criticised the Government for what it called “misinformation”.

Urging ministers to focus on heat pumps instead, it wrote: “Hydrogen is not a serious option for home heating in the short to medium-term and its use is expected to be limited in the long-term.”

Even HyNet’s David Parkin conceded the point in his interview with LBN. He said: “People will say heat pumps are more efficient than hydrogen and it is hard to argue with the basic physics of that.

“One unit of electricity from an offshore wind farm into a heat pump you can get three units of heat. If you get that same unit into an electrolyser and put the hydrogen into a pipe and burn it in a boiler, you might get half a unit of heat.”

But he added: “If you have regions where you are using hydrogen in industry anyway then you might roll it out in those regions. Or you might see a hybrid heat pump that can use both electricity and hydrogen.

“We won’t know for definite until we conduct more trials. What we are doing in Whitby is demonstrating the viability. It will also come down to what consumers want.”

Industry is main aim

Hydrogen for industrial use remains the primary objective of HyNet and those factories who have signed the agreements are enthusiastic about the prospect.

Encirc in Cheshire supplies around a third of all glass bottles and containers made for the UK and Republic of Ireland each year. It will be taking 300MW of hydrogen.

Managing director Adrian Curry said: “This partnership with Vertex Hydrogen will help us to change the face of glass as we aim to produce net zero bottles by 2030.

“Glass is an incredible material and sustainable in so many ways. It has been around since 3500 BC, and by using hydrogen to decarbonise it, we believe it will be the packaging choice for centuries to come.”

Pilkington in St Helens has already participated in a number of trials using hydrogen to power its glass making furnace facilities.

Neil Syder, managing director of Pilkington UK, said: “We are fully committed to our NSG Group target of achieving carbon neutral by 2050. Firing the float glass furnace using hydrogen instead of natural gas is a key part of our strategy to reduce carbon emissions.

And Prashant Ruia, from Essar, also said: “Securing over 1000MW of low carbon hydrogen demand from leading UK industrial sites and innovators is a vital step in delivering this world class project.

“Essar continues to invest in an array of industry leading projects from hydrogen production, biofuels, industrial decarbonisation and infrastructure leveraging our infrastructure, expertise, capital and desire to be a world leader in decarbonisation.”